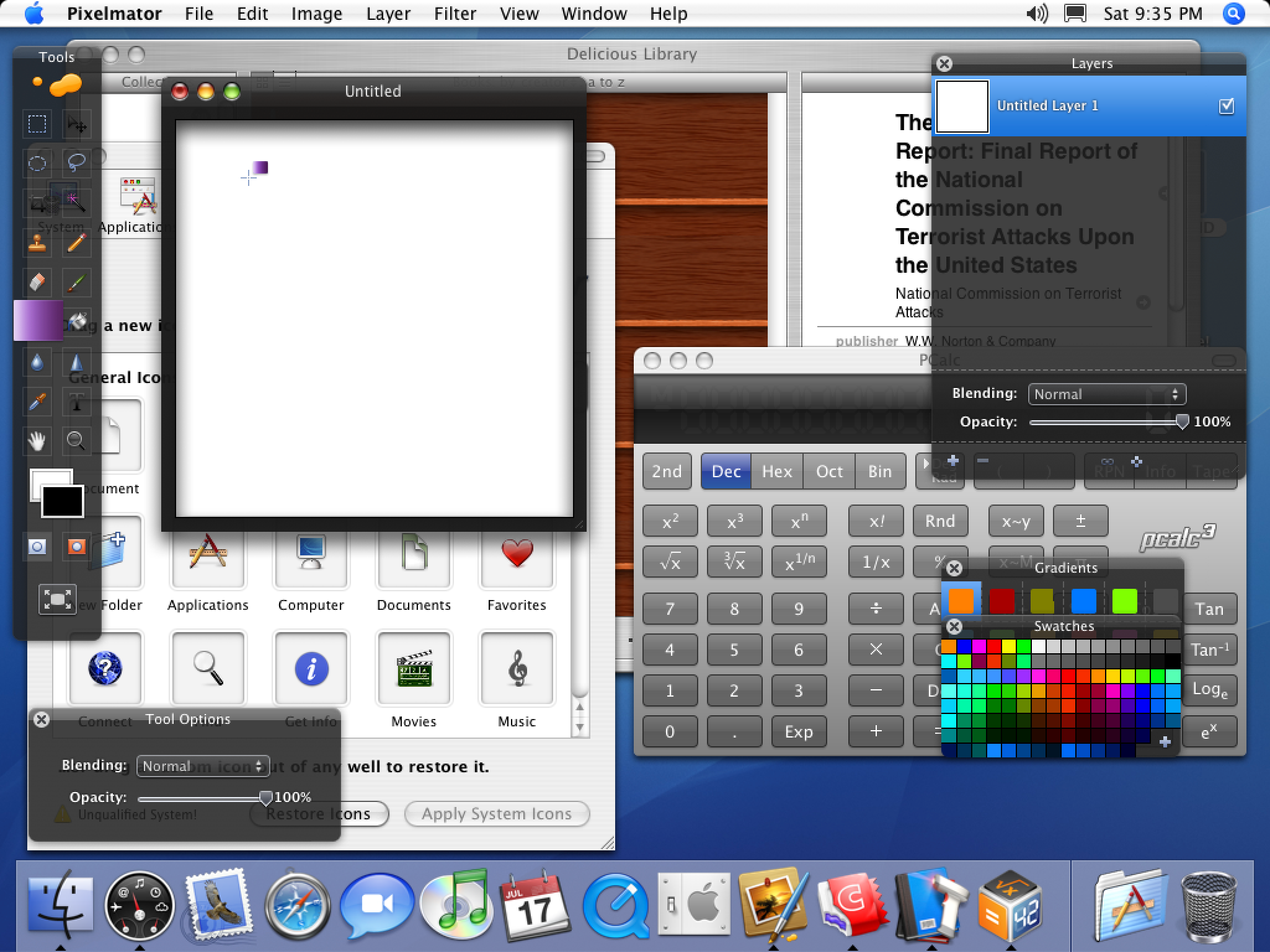

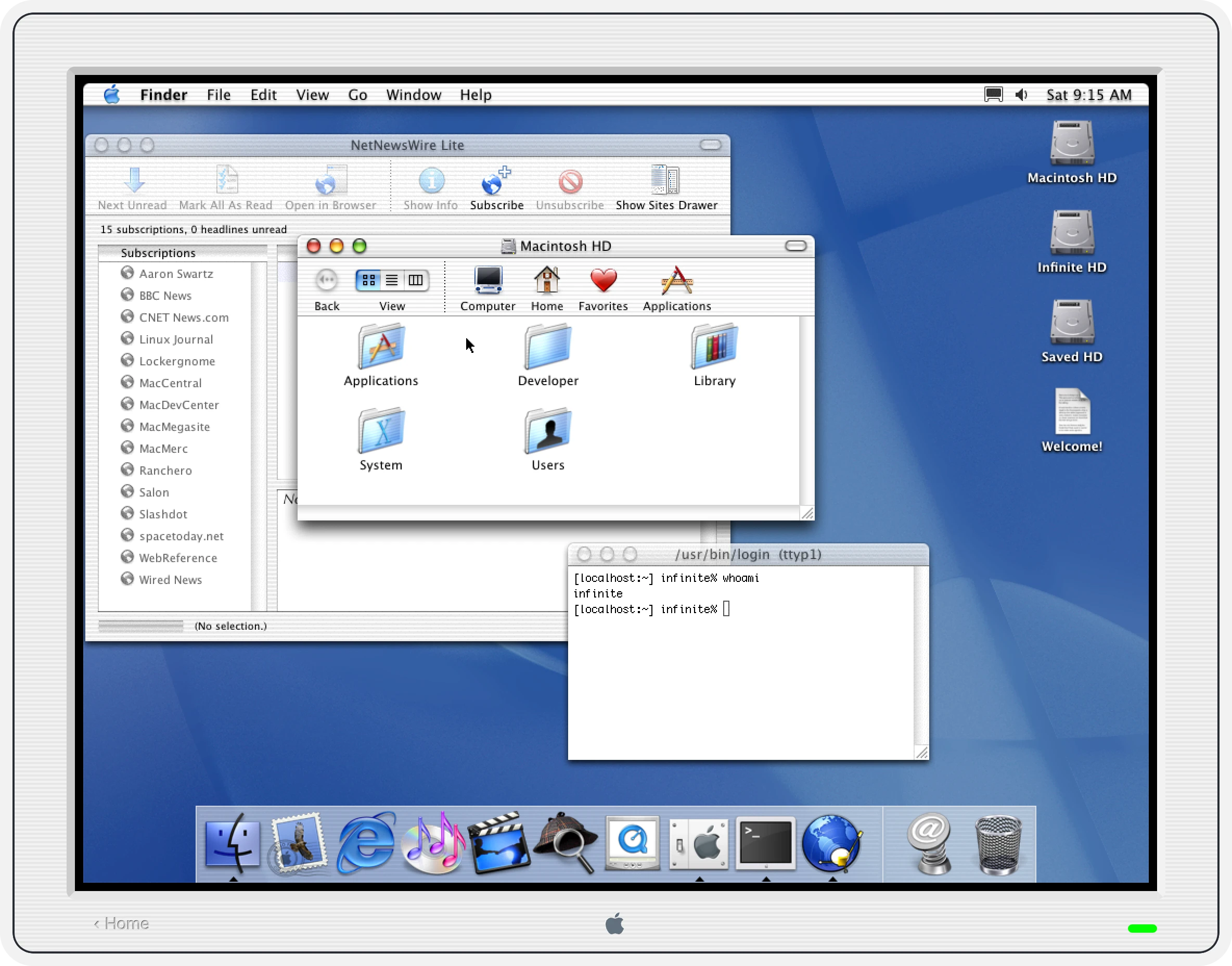

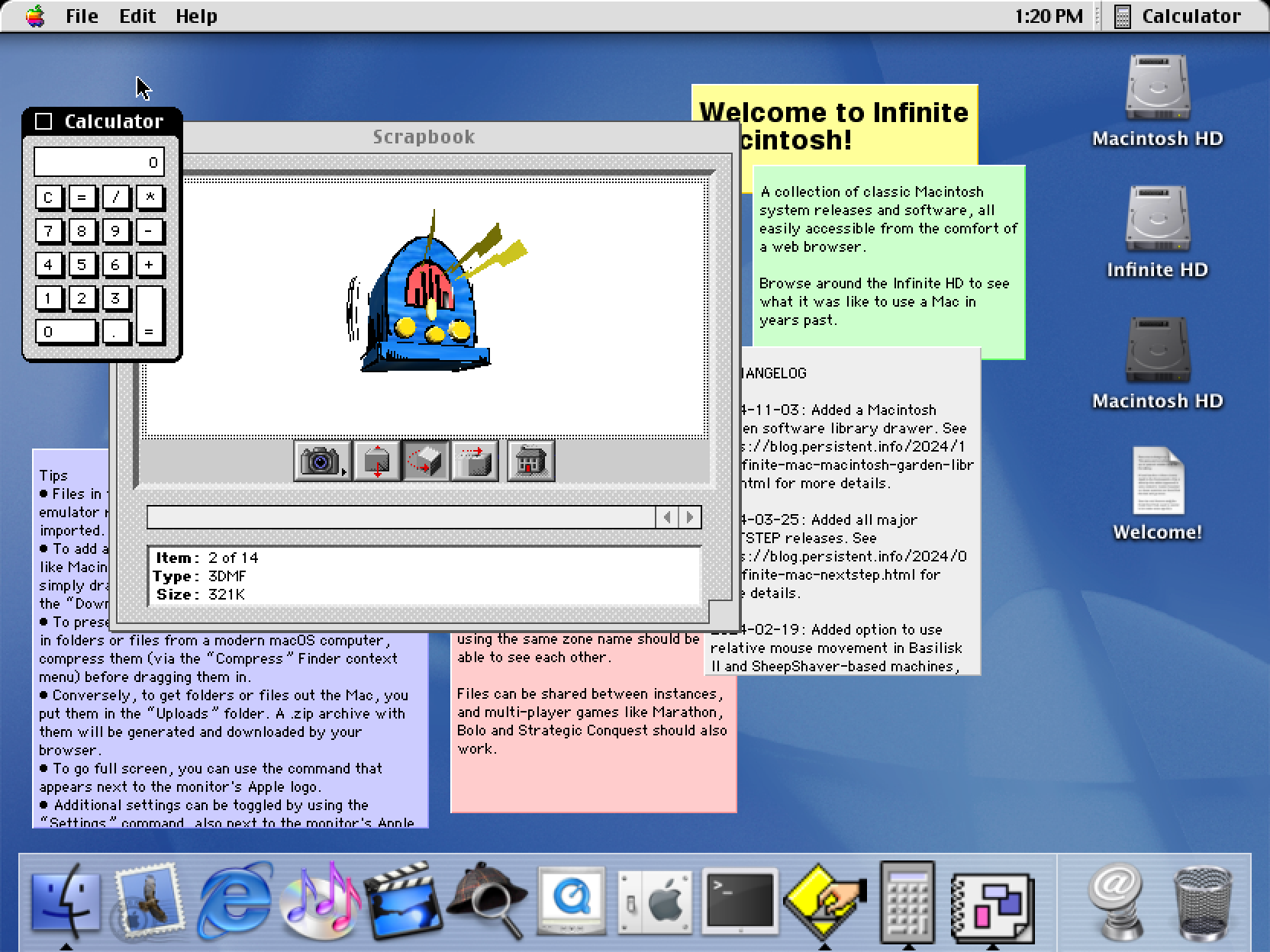

tl;dr: Infinite Mac can now run early Mac OS X, with 10.1 and 10.3 being the best supported versions. It’s not particularly snappy, but as someone who lived through that period, I can tell you that it wasn’t much better on real hardware. Infinite HD has also been rebuilt to have some notable indie software from that era.

Porting PearPC

I’ve been tracking DingusPPC progress since my initial port and making the occasional contribution myself, with the hope of using it to run Mac OS X in Infinite Mac. While it has continued to improve, I reached a plateau last summer; my attempts would result in either kernel panics or graphical corruption. I tried to reduce the problem a bit via a deterministic execution mode, but it wasn’t really clear where to go next. I decided to take a break from this emulator and explore alternate paths of getting Mac OS X to run.

PearPC was the obvious choice – it was created with the express purpose of emulating Mac OS X on x86 Windows and Linux machines in the early 2000s. By all accounts, it did this successfully for a few years, until interest waned after the Intel switch (sadly one of the authors passed away around then). I had earlier dismissed it as a “dead” codebase, but I decided that the satisfaction of getting something working compensated for dealing with legacy C++ (complete with its own string class, sprintf implementation, and GIF decoder). An encouraging discovery was that kanjitalk755 (the de-facto Basilisk II and SheepShaver maintainer) had somewhat recently set up an experimental branch of PearPC that built and ran on modern macOS. I was able to replicate their work without too much trouble, and with that existence proof I started on my sixth port of an emulator to WebAssembly/Emscripten and the Infinite Mac runtime.

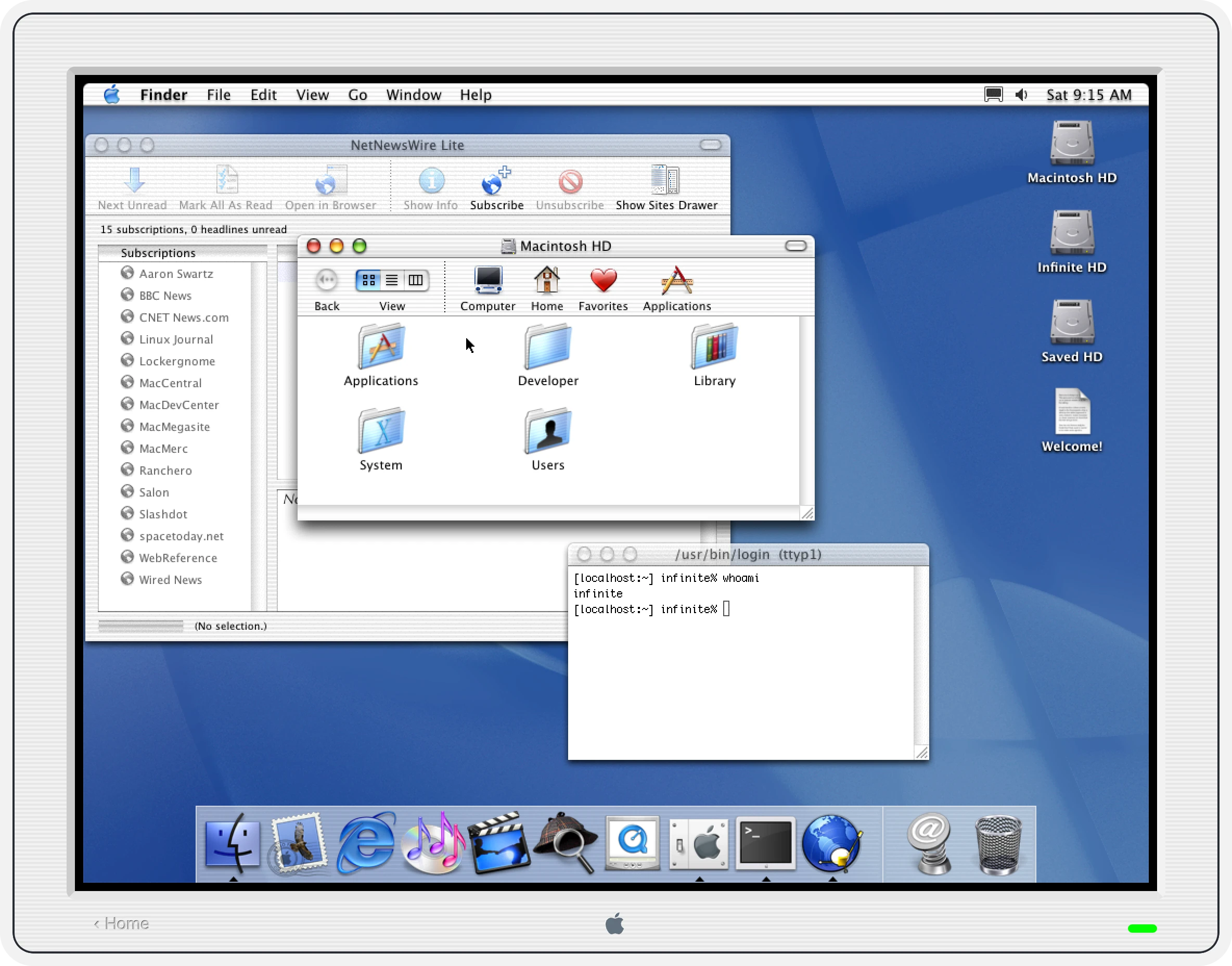

In some ways PearPC not being actively developed made things easier – I didn’t have to worry about merging in changes from upstream, or agonize over how to structure my modifications to make them easier to contribute back. It was also helpful that PearPC was already a multi-platform codebase and thus had the right layers of abstraction to make adding another target pretty easy. As a bonus, it didn’t make pervasive use of threads or other harder-to-port concepts. Over the course of a few days, I was able to get it to build, output video, load disk images, and get mouse and keyboard input hooked up. It was pretty satisfying to have Mac OS X 10.2 running in a browser more reliably than it previously had.

Performance

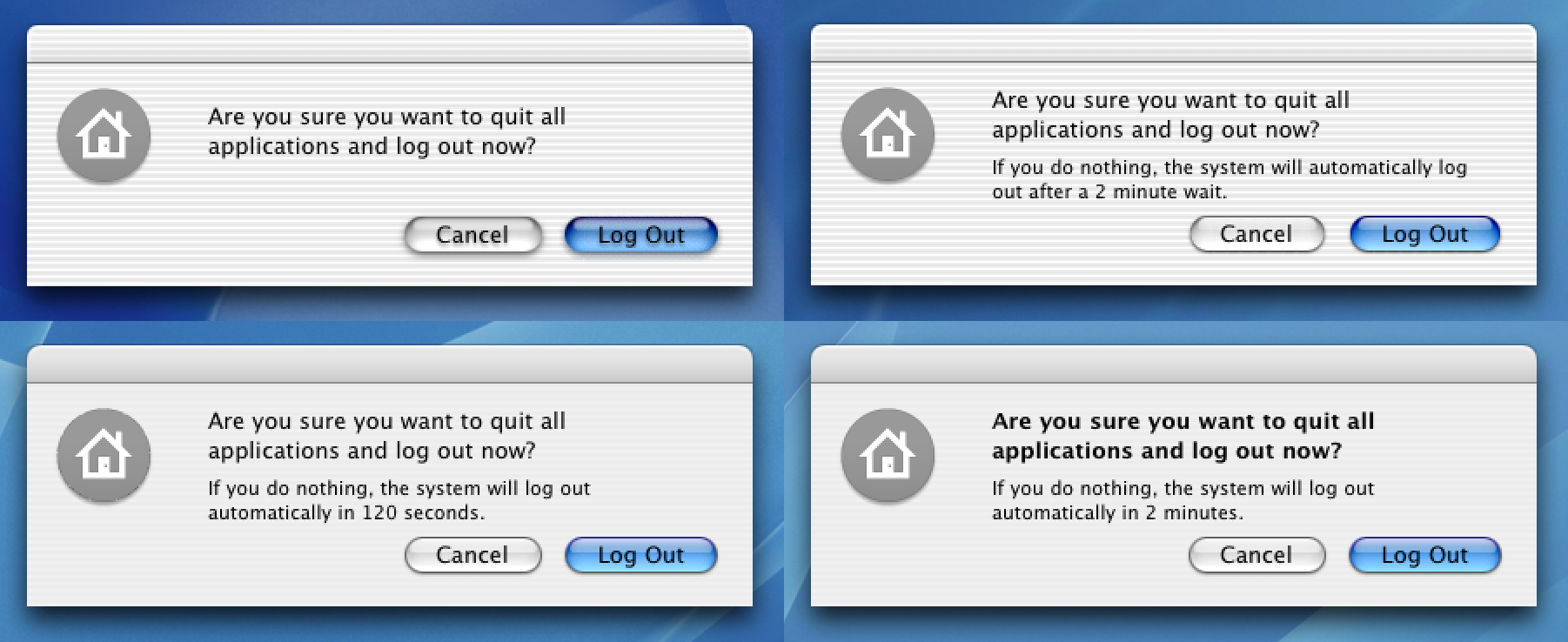

While PearPC ran 10.2 more reliably, it felt slower than DingusPCC. I had spent some time last year making some optimizations to the latter, partly inspired by the TinyPPC emulator in this SheepShaver fork (aren’t all these names fun?). I ported DingusPPC’s benchmark harness and then set about replicating the performance work in PearPC (both emulators are pure interpreters driven by a lookup table, so the process was relatively straightforward). I was able to shave off about 15 seconds from the 10.2 boot time – it helps from a saving lives perspective, but is still not enough given that it takes almost 2 minutes to be fully operational. In the end, I copped out and added a UI disclaimer that Mac OS X can be slow to boot. I also got flashbacks to the “is it snappy yet?” discussions from the early days of Mac OS X – it was indeed slow, but not this slow.

Performance is still not as good as DingusPPC’s – the biggest bottleneck is the lack of any kind of caching in the MMU, so all loads and stores are expensive since they involve complex address computations. DingusPPC has a much more mature tiered cache that appears to be quite effective. More generally, while PearPC may be more stable than DingusPPC at running 10.2-10.4, it’s a much less principled codebase (I came across many mystery commits) and it “cheats” in many ways (it has a custom firmware and video driver, and only the subset of PowerPC instructions that are needed for Mac OS X are implemented). I’m still holding out hope for DingusPPC to be the fast, stable, and correct choice for the long term.

A Side Quest

I implemented the “unified decoding table” approach in PearPC’s interpreter one opcode family at a time. When I got to the floating point operations, I assumed it was going to be another mechanical change. I was instead surprised to see that behavior regressed – I got some rendering glitches in the Dock, and the Finder windows would not open at all. After some debugging, I noticed that the dispatching for opcode groups 59 and 63 didn’t just do a basic lookup on the relevant instruction bits. It first checked the FP bit of the Machine State Register (MSR), and if it was not set it would throw a “floating point unavailable” exception.

I initially thought this was the emulator being pedantic – all PowerPC chips used in Macs had an FPU, so this should never happen. However, setting a breakpoint showed that the exception was being hit pretty frequently during Mac OS X startup. The xnu kernel sources of that time period are available, and though I’m not familiar with the details, there are places where the FP bit is cleared and a handler for the resulting exception is registered. I assume this is an optimization to avoid having to save/restore FPU registers during context switches (if they’re not being used). The upshot was that once I implemented the equivalent FP check in my optimized dispatch code, the rendering problems went away.

This reminded me of the rendering glitches that I had encountered when trying to run Mac OS X under DingusPPC. Even when booting from the 10.2 install CD (which does not kernel panic) I would end up with missing text and other issues:

Checking the DingusPPC sources showed that it never checked the FP bit, and always allowed floating point instructions to go through. I did a quick hack to check it and raise an exception if needed, and the glitches went away!

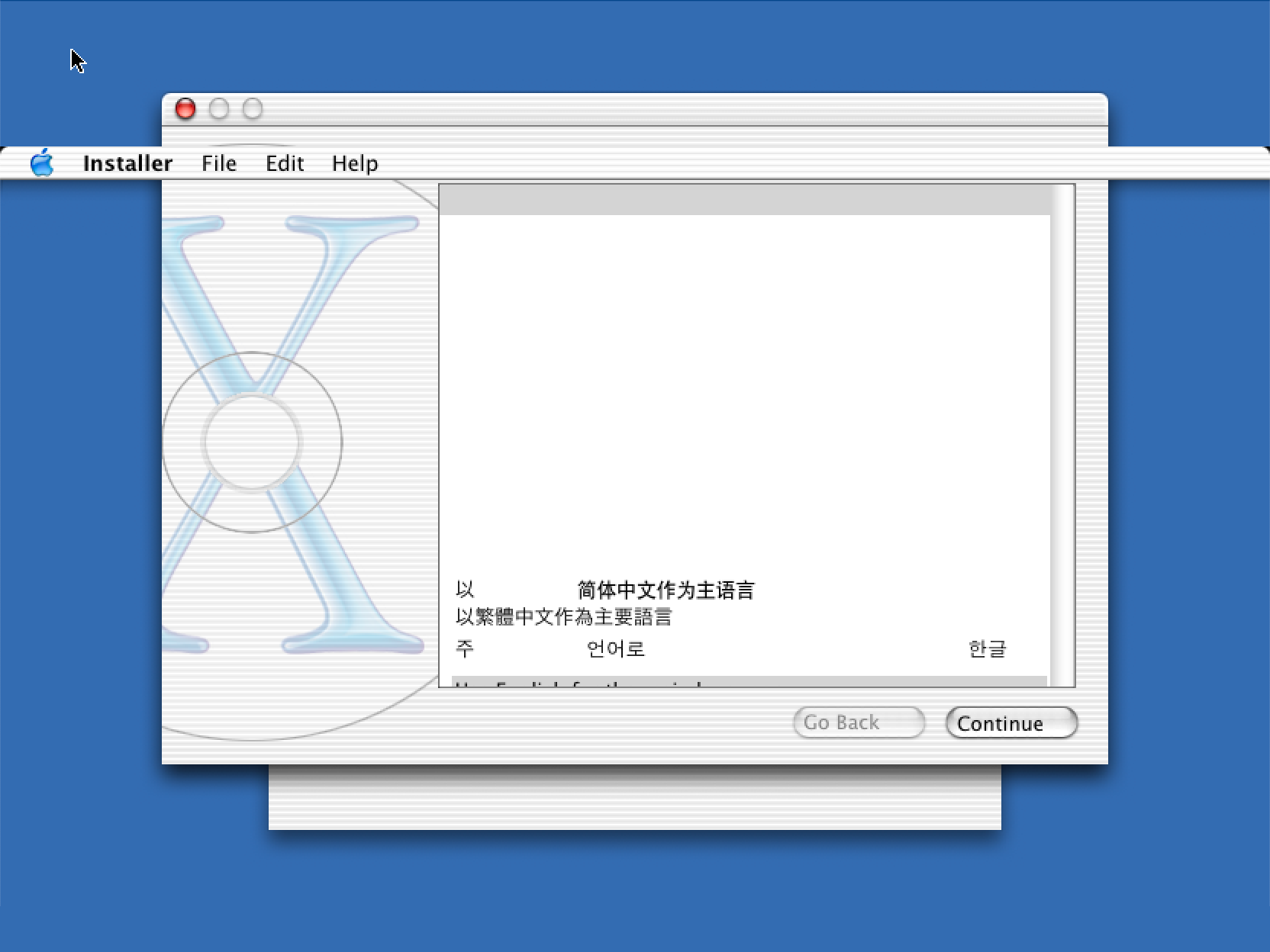

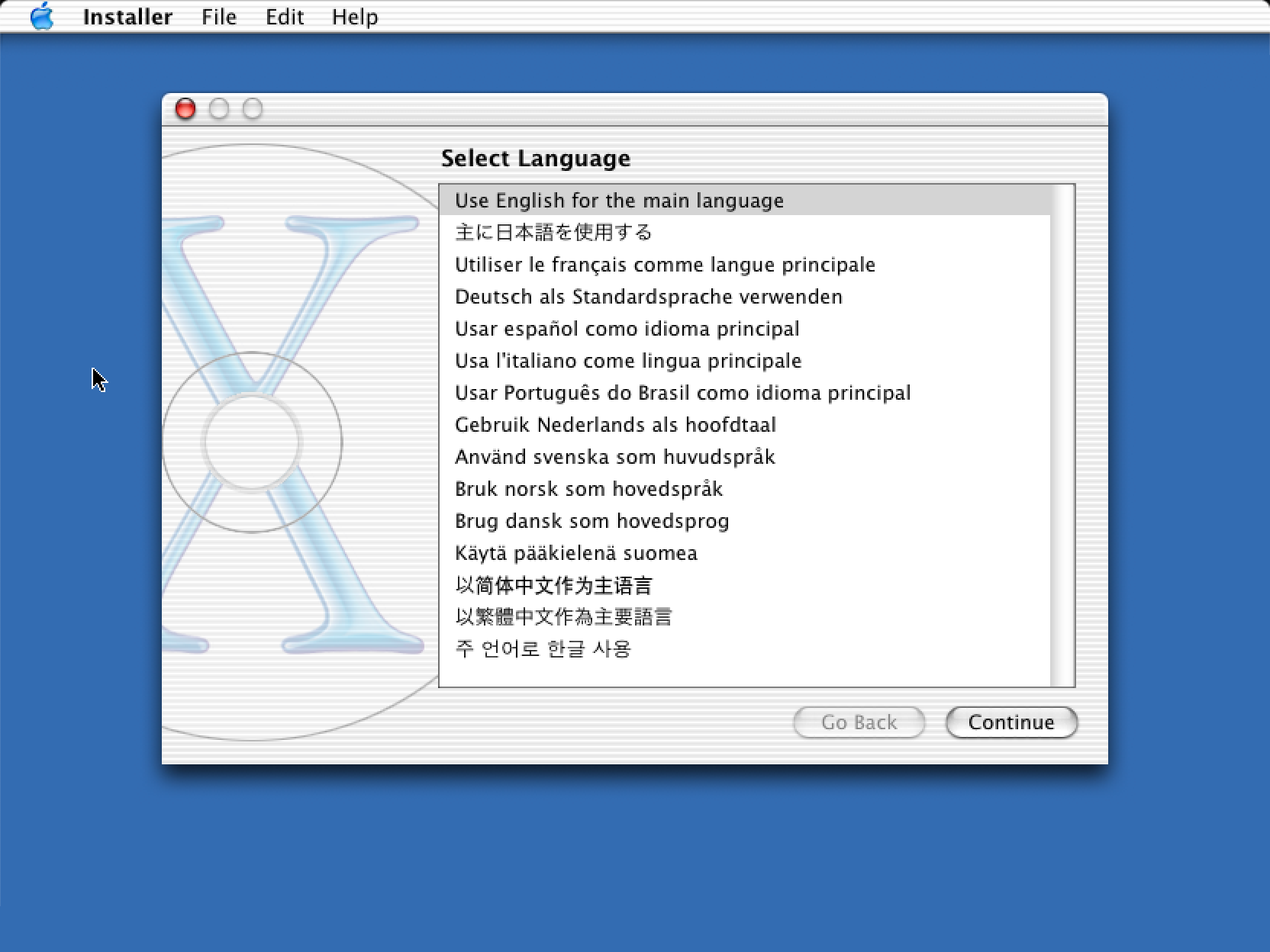

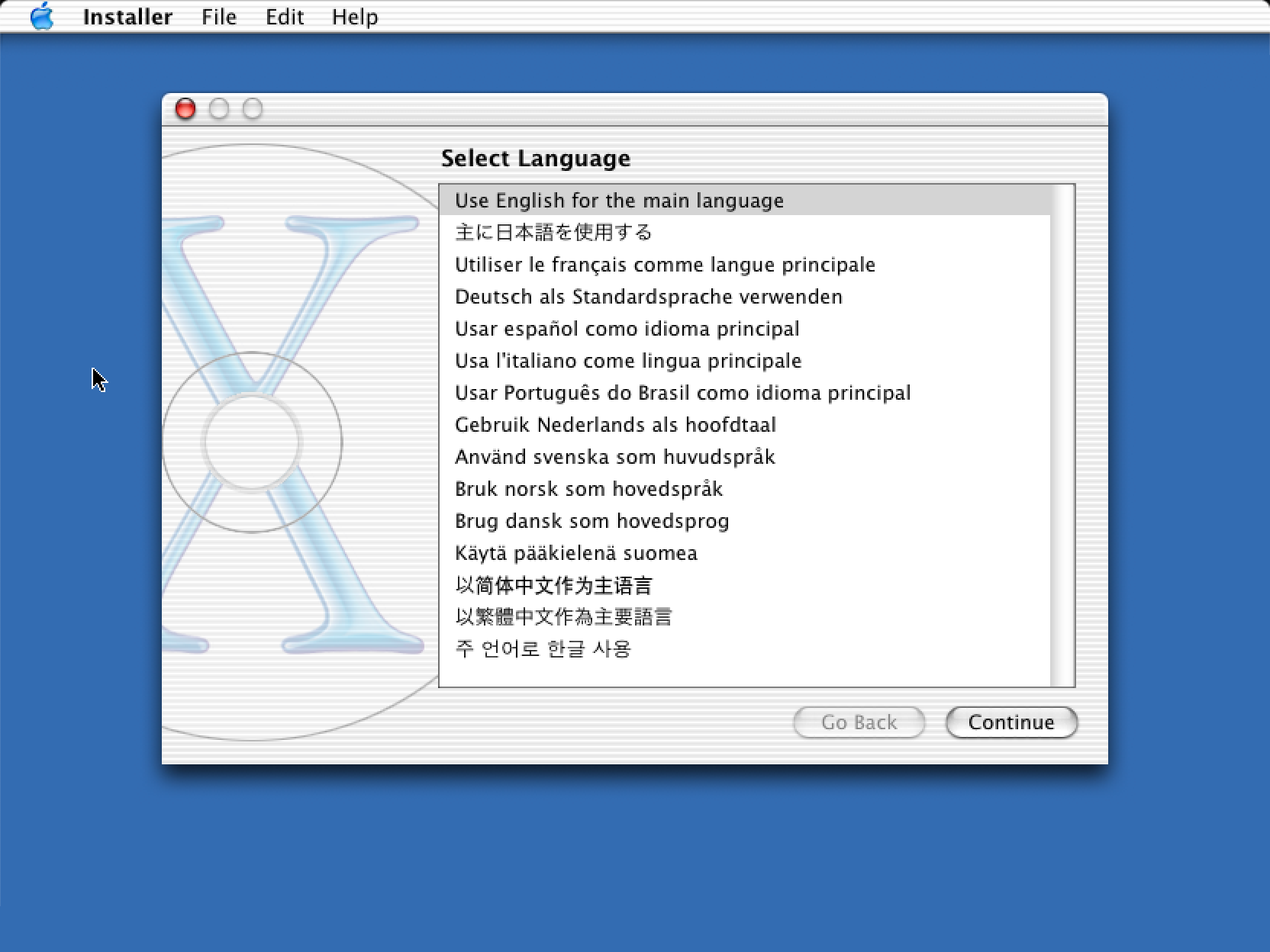

The proper implementation was a bit more complicated, and I ended up revising it a bit to avoid a performance hit (and another contributor did another pass). But at the end of it all, DingusPPC became a lot more stable, which was a nice side effect. Better yet, it can run 10.1 reliably, which PearPC cannot. I ended up using a combination of both emulators to run a broader subset of early Mac OS X (unfortunately 10.0 is still unstable, and the Public Beta kernel panics immediately, but I’m holding out hope for the future).

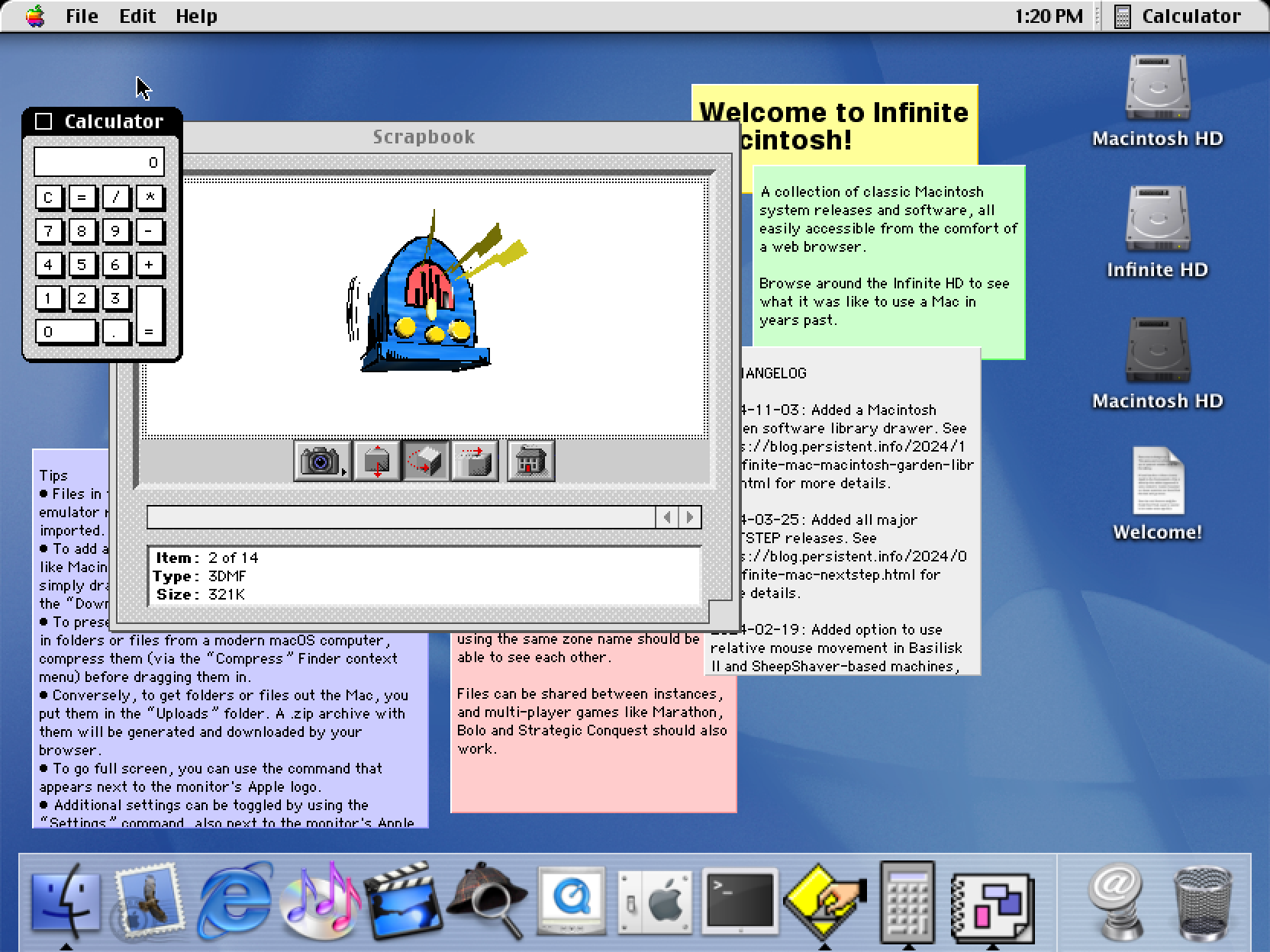

Rebuilding Infinite HD

Part of the appeal of Infinite Mac is that the emulated machines also have an “Infinite HD” mounted with a lot of era-appropriate software to try. With Mac OS X running, it was time to build an alternate version that went beyond the 80s and 90s classic Mac apps I had collected. I had my favorites, but I also put out a call for suggestions and got plenty of ideas.

For actually building the disk image, I extended the automated approach that I first launched the site with. Disk images were even more popular in the early days of Mac OS X than they are today, so I added a way to import .dmgs as additional folders in the generated image. However, I quickly discovered that despite having the same extension, there are many variants, and the hdiutil that ships with modern macOS cannot always mount images generated more than 20 years ago. In the end I ended up with a Rube Goldberg approach that first extracts the raw partition via dmg2img and then recreates a “modern” disk image that can be mounted and copied from.

As for getting the actual software, the usual sites like Macintosh Garden do have some from that era, but it’s not a priority for them. Early to mid 2000s Mac OS X software appears to be a bit of a blind spot – it’s too new to be truly “retro”, but too old to still be available from the original vendor (though there are exceptions). I ended up using the Wayback Machine a lot. As a bonus, I also installed the companion “Developer” CDs for each Mac OS X version, so tools like Project Builder and Interface Builder are also accessible.

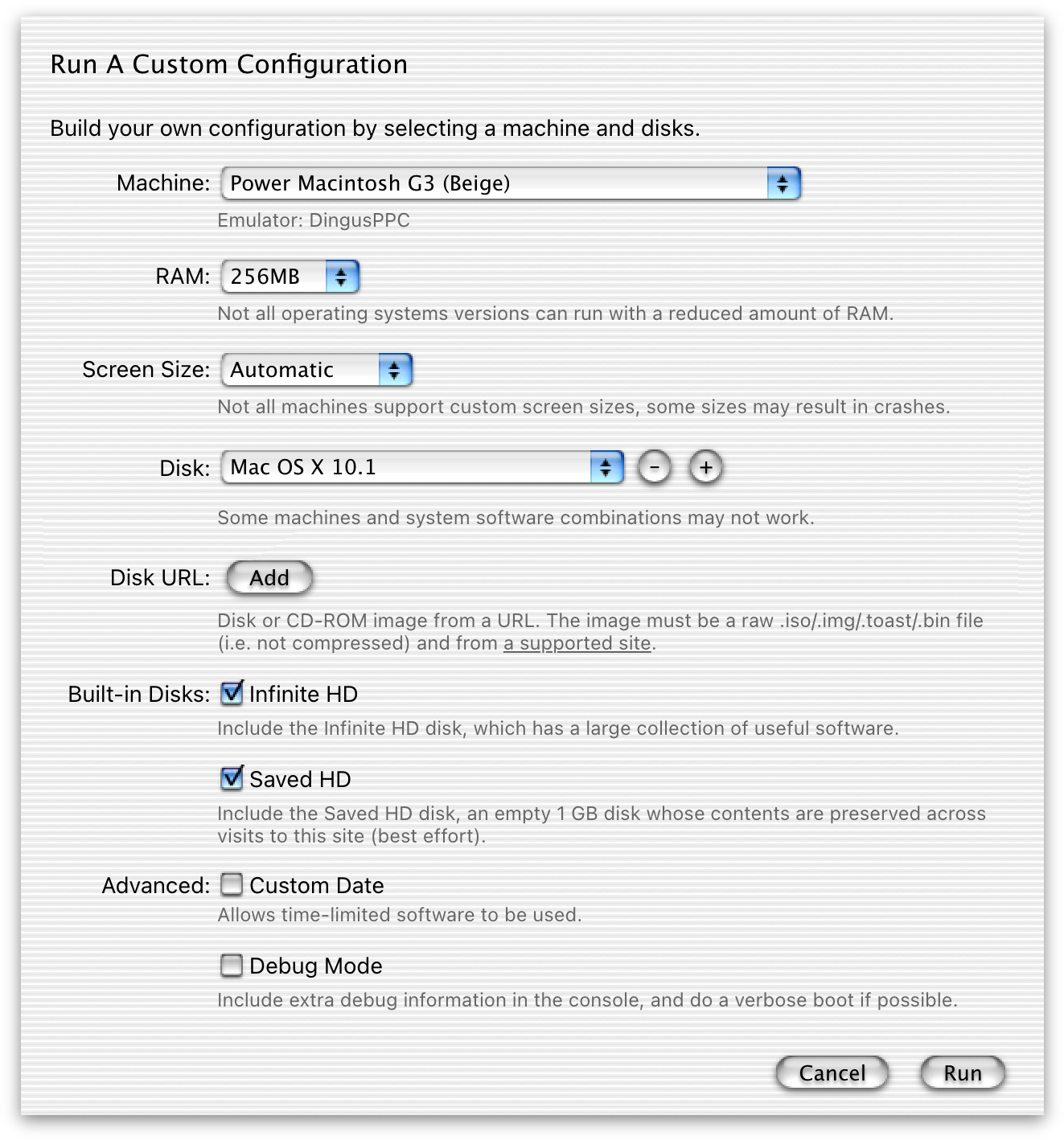

The only limitation that I ran into is that my disk build process is centered around HFS, but HFS+ was the default of that time period, and it introduced more advanced capabilities like longer file names containing arbitrary Unicode characters. Files from disk images that rely HFS+ features do not translate losslessly, but luckily this was not an issue for most software. To actually mount multiple drives (up to 3, between the boot disk, Infinite HD, and Saved HD), I ended up borrowing a clever solution from a DingusPPC fork: a multi-partition disk image is created on the fly from an arbitrary number of partition images that are specified at startup.

Aqua

To make the addition of Mac OS X to Infinite Mac complete, I also wanted to have an Aqua mode for the site’s controls, joining the classic, Platinum, and NeXT appearances. That prompted the question: which Aqua?

Aqua: the early years

Though the more subdued versions from 10.3 and 10.4 are my favorites, I decided to go with the 10.0/10.1 one since it has the biggest nostalgia factor. I wanted to use the exact same image assets as the OS, and since they make heavy use of semi-transparency, regular screenshots were not going to be good enough. I used resource_dasm and pxm2tga to extract the original assets from Extras.rsrc and create my own version of Aqua:

If the recent rumors of a big UI revamp do come true, it’ll be nice to have this reference point of its ancestor.

Odds and Ends

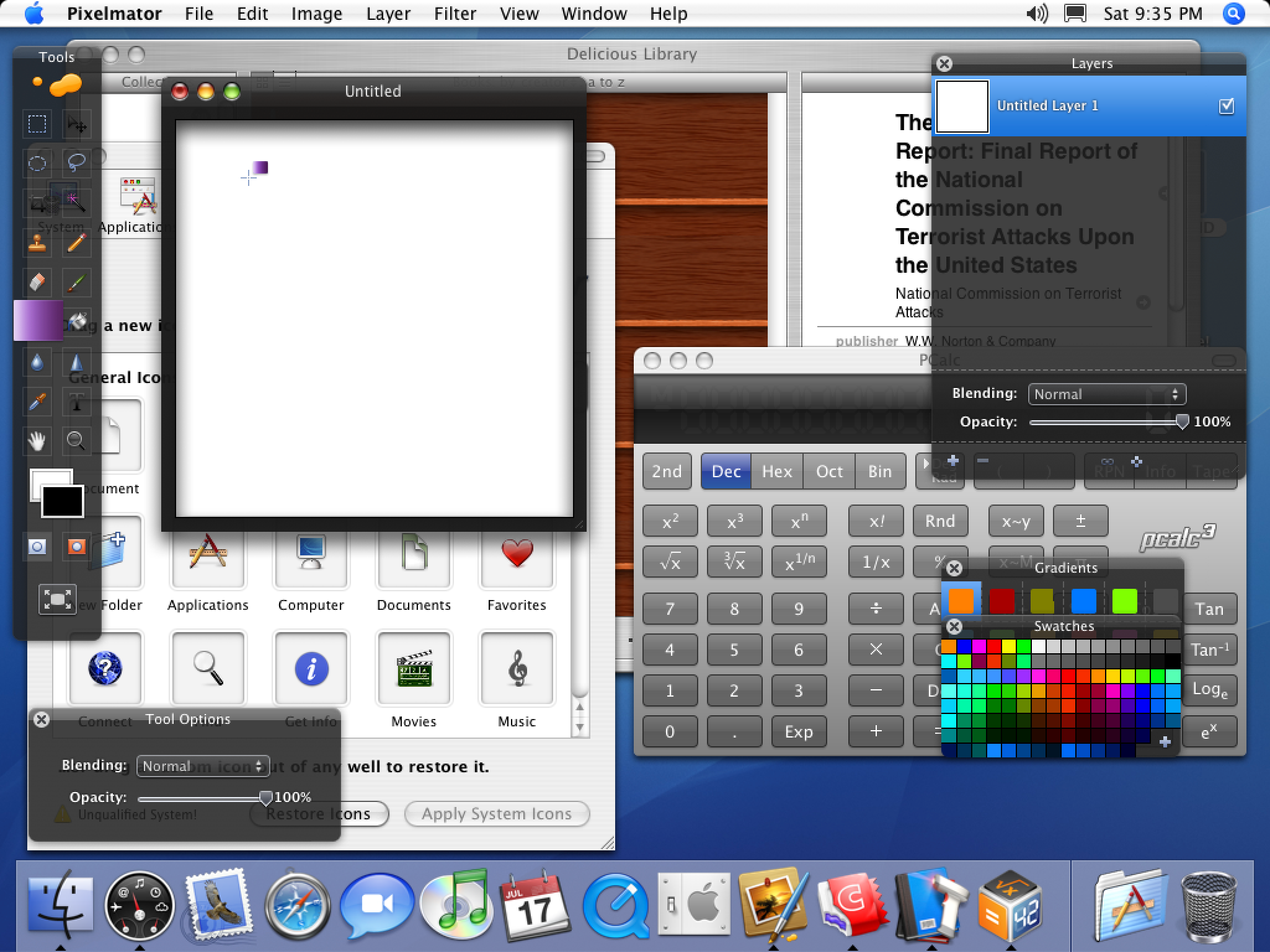

The ability to mount multiple images means that you can also have a Mac OS 9 partition and start the Classic compatibility environment (this only works under 10.1 – PearPC never supported Classic). You can thus emulate classic Mac apps inside an emulated Mac OS X inside a WebAssembly virtual machine:

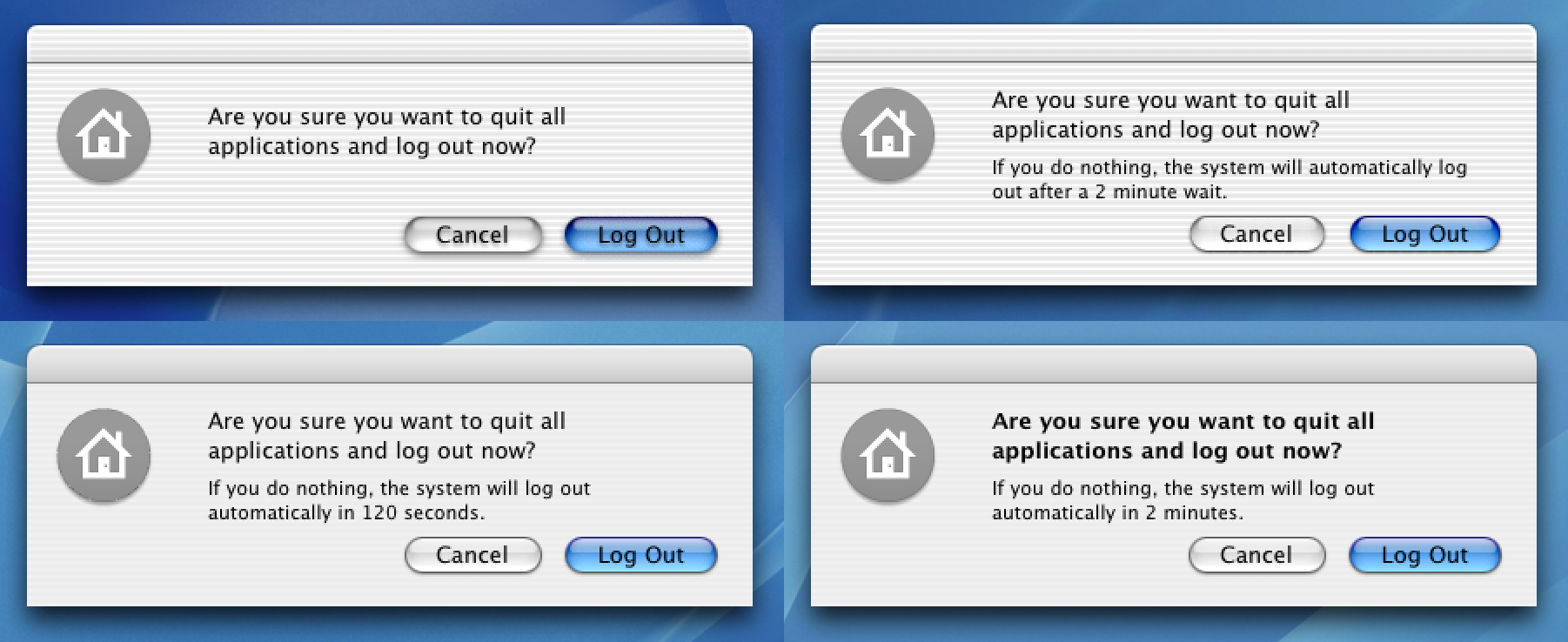

There was a recent storm in a teacup about a Calculator behavior change. Using these Mac OS X images, it’s possible to verify that versions through 10.3 didn’t have the “repeatedly press equals” behavior, but 10.4 did.

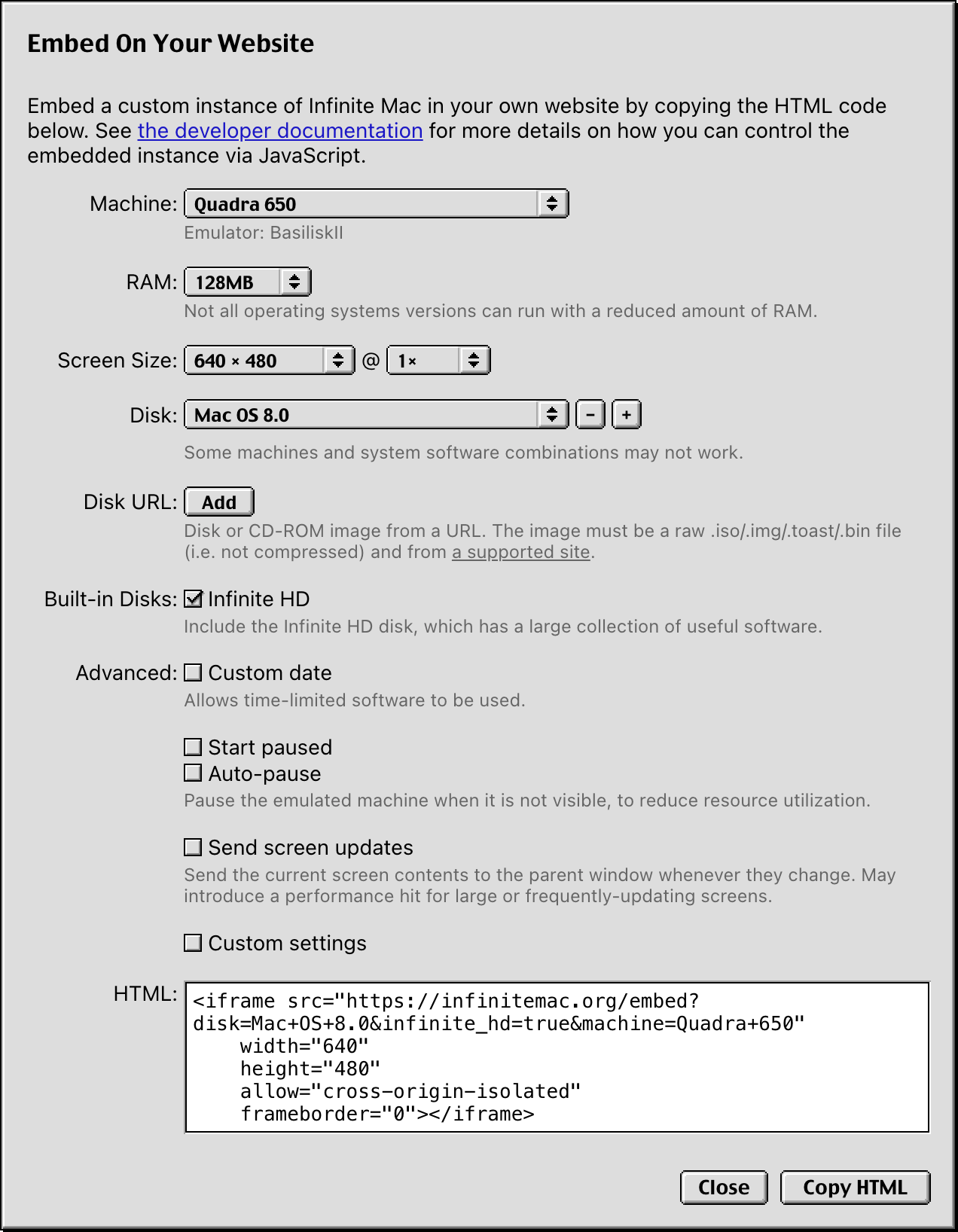

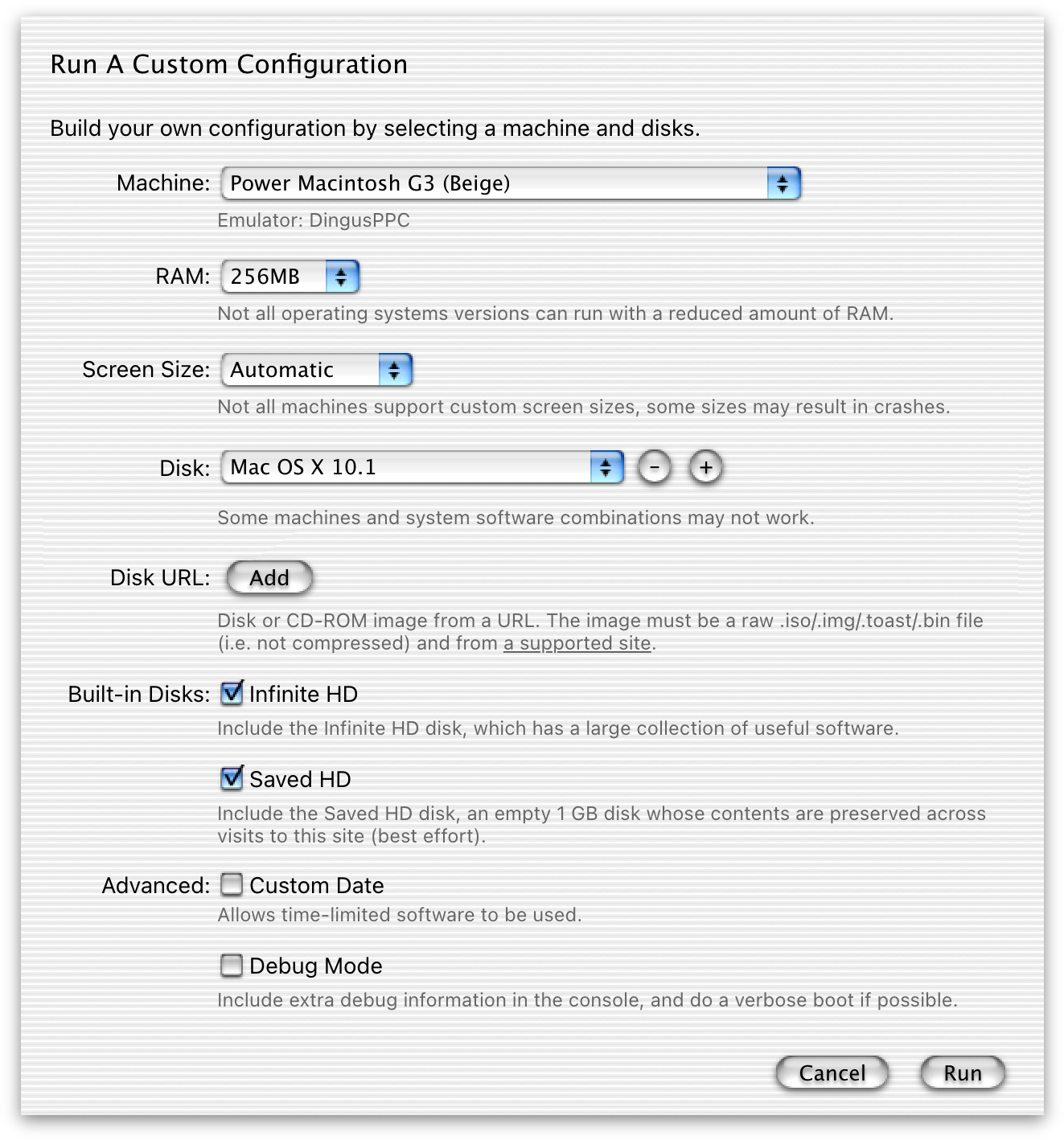

Since Mac OS X boot is rather slow, I wanted to have a way to show more progress. PearPC has a built-in way to trigger verbose mode, but DingusPPC did not, so I added a way to specify Open Firmware variables at startup. This is now exposed in the custom instance dialog via the “Debug Mode” switch.

Though I’ve moved away from custom domain names, I thought macosx.app would make a nice addition to my collection. Unfortunately it’s taken, though in a rather weird way. I even contacted the YouTuber whose video it redirects to, and he said he was not the one that registered it. It expires in a couple of months, so maybe I’ll be able to grab it.

The End Of The Line?

“When Alexander saw the breadth of his domain, he wept for there were no more worlds to conquer.”

— Hans Gruber Plutarch Some Frenchman

Mac OS X support catches Infinite Mac up to the modern day, unless I happen to get access to some time travel mechanics. There are of course two more CPU transitions to go through and numerous small changes, but Tiger is fundamentally recognizable to any current-day macOS user.

Except that in the retrocomputing world, it’s always possible to go deeper or more obscure. A/UX is not something that I’m very familiar with, but it was a contemporary of classic Mac OS and would be interesting to compare to NeXTStep. Shoebill runs it, and the codebase looks approachable enough to port. Then there’s Lisa, the Pippin (DingusPPC has some nascent support), and further afield the Newton (via Einstein?). We’ll see what moves me next.

A Post-Credits Sequence

When I first began exploring ways of running Mac OS X, I mentioned that QEMU seemed too daunting to port to WebAssembly given my limited time. Furthermore, the performance of the qemu.js experiment from a few years ago made it seem like even if it did run, it would be much too slow to be usable. However, I recently became aware of qemu-wasm via this FOSDEM presentation. The performance of its Linux guest demos is encouraging: I ran an impromptu bennmark of computing an MD5 checksum of 100 MB of data and it completed it in 8 seconds (vs. 13 for DingusPPC and 18 for PearPC). There’s still a big gap between that and a graphical guest like Mac OS X, but it’s nice to have this existence proof.

Update: See also the discussion on Hacker News.